Withdrawing from Erasmus is a travesty for poorer kids

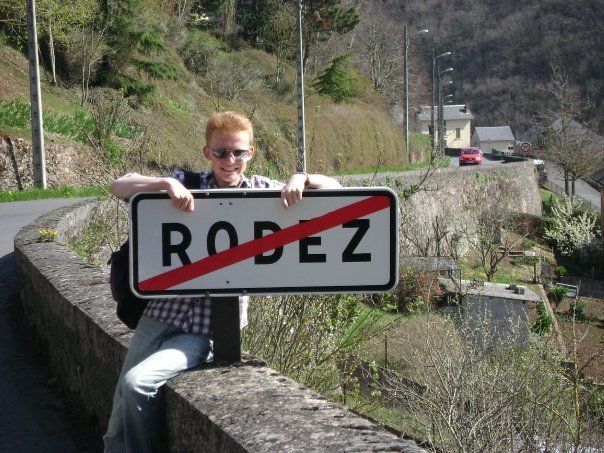

I stood in the staff room, sipping a vending machine espresso, giddy with caffeine and nerves. It was autumn 2008, and my first day of teaching in a French lycée in the rural, southwestern town of Rodez. “ They’re going to be so excited to meet you ”, Danielle, my mentor, assured me, as we strode along the corridor to the classroom after morning breaktime. As we moved, crowds of noisy teenagers parted amid whispers of “ qui est-ce? ” and my self-consciousness soared. Arriving in the classroom, students filed in and took their seats, before Danielle introduced me. “ This is Simon, our new English language assistant.” Thirty pairs of eyes studied me furiously.

I had no idea what my year abroad would be like. I’d received advice from veterans of the Erasmus+ scheme, led by the British Council, before departure, but frankly, as the first ever in my family to attend university out of school – my mum studied nursing as a mature student while I was at school – the whole higher education experience was so alien to me that it might as well have been advice for moving to Mars.

I grew up in Innerleithen and Peebles in the Scottish Borders. My family were never rich. We weren’t destitute either, but my parents’ separation and divorce in 1996-7 saw us all much worse off financially. My brother, sister and I ended up in homeless accommodation with our mum, where we lived for eighteen months before we could get a proper council house. While money might have been tight for my childhood, one thing my parents were never, ever short of was encouragement for their children to “stick in” at school – they knew that a decent education was how we would get ahead in life in a post-industrial Scotland. Had I been born twenty years earlier, it would probably have been a job in machine knitting at the mill for me, following in my dad and grandad’s footsteps. But that industry was on its way out. So with the support and fierce encouragement of my parents and grandparents, I did as I was told and stuck in at school. When I got to high school, I began to excel in languages – French, German and Spanish – and it was my wonderful French teacher, Mrs Robertson, who first lit the fire in my mind that I could apply to study languages at university.

When I got an unconditional offer in 2006 from St Andrews to study French and German with an integrated year abroad, I was torn. Thrilled, yes. Elated, yes. But terrified. Nobody I knew could tell me anything about university, and certainly not about working or studying abroad. Spotting my interest in politics and my passion for languages, my school guidance teacher convinced me that with a language degree, I could “go and work in Brussels one day – that’s where the future is”, and – despite how that has worked out for the UK now – that hazy possibility was what drove me. Truth be told, I didn’t honestly know what I was doing. After all, who does at sixteen, seventeen? But I was academic rather than practical and, as I didn’t want to stay in Peebles forever, uni felt like the right choice.

When I got to university, I didn’t have much money. My family were not in a strong position to support me in the way that many folk around me were supported. The post-exam January break, known in the middle class St Andrews bubble as “ski week”, was something I could never live out. That's when I realised I was relatively poor - when it was thrust in my face and I had to turn down offers of holidays. Accommodation was expensive, even in the cheapest and most basic halls, and after paying that out of my student loan and SAAS grant, there wasn’t much left each semester. During freshers’ week I found out I was invited to attend a scholarship awards ceremony. Me being me, I had no idea what a scholarship was. Some other weird part of matriculation, I assumed, and went along. I was presented with a certificate, and a letter, and (I later realised) a cheque for £1000, which I promptly filed away for thirteen years. Yes – I missed out on a scholarship for low income students because I didn’t know what a scholarship was. Nobody explained it to me, a kid from a family with no knowledge of university whatsoever, and I didn’t see the cheque buried in all the heaps of bewildering paperwork that go with matriculation.

When it came to my third year, the impending prospect of going abroad for a year was petrifying. I barely managed to cover the expense of living in St Andrews, seventy-five miles from home. How would I afford the flights, the accommodation, living costs and all the rest of it? There were so many unknowns. Suddenly it was looking like a very risky idea. The day before I was due to fly out, I had a bit of a breakdown, concerned about money and leaving my friends. But fly out it I did, and a week later I was standing at the front of that classroom as an assistant d’anglais .

Erasmus has long been taken advantage of by more affluent students. That makes it no different from the entirety of higher education in the UK. Young people from richer backgrounds know about these things because their parents went to uni, or their cousin did Erasmus. They know about university; they know about Erasmus; they know about scholarships. They know about jobs and openings and internships and opportunities that their poorer peers do not. Put simply, they know because they are well-connected in a way that many of them take for granted. The language of the higher education system is their language. It wasn’t mine when I started out.

Once I got settled in France, I realised that in addition to my loan payment and SAAS grant, I’d be paid approximately €800 per month for my work in the schools. This would more than cover my flights home at Christmas and Easter, I thought. Then, to my delight while flat-hunting, I realised that, since I was under twenty-five, the French government would subsidise seventy per cent of my monthly rent costs, meaning I paid just €170 a month for my cosy attic flat with a skylight window looking up onto the mediaeval cathedral bell tower in the heart of the town.

For a year I lived like a king. My confidence grew in the classroom and I developed a strong relationship of trust and respect with my students. My French improved immeasurably through total immersion in the language and culture. I was even able to do a bit of travelling, heading down to the Pyrenees to ski in January with new colleagues and friends. I recall spending rainy Saturday afternoons in autumn, wandering through forests collecting chestnuts to roast, or tutoring the kids of some of my colleagues in English for a bit of extra pocket money. Every weekend I feasted on local cheese and wine from the farmers’ market in the square outside my flat. That year was the most enriching experience of my life, and it very nearly didn’t happen.

I didn’t think any of my Erasmus year was possible. I couldn’t ever even have imagined it until I had lived it. At so many points in my life, I could have taken another, more comfortable path. What if I hadn’t had an encouraging French teacher? What if my parents hadn’t convinced me to stick in at school? What if I’d decided, on the spur of the moment on the eve of my departure for France, that I was just going to sit the year abroad out because I was worried about cash?

That’s what happens to so many young people from less well-off backgrounds. It is not that they are less capable, or even in many cases, less able to afford the opportunities offered by Erasmus (because as I discovered, these schemes are well-funded). Neither is the Erasmus scheme itself a failure; it's a glorious thing, and a triumph of European cooperation. The problem is that society’s safety net is full of holes. We do not give all young people the information and knowledge that they need, in a language they understand, to be able to make life-changing choices like Erasmus.

The UK’s withdrawal from the Erasmus scheme is a travesty. The Prime Minister has said that our participation in Erasmus is “extremely expensive” and has announced the so-called Turing Scheme, which is to be “bigger and better” yet somehow also cheaper. Maybe he'll claim it's "world-beating", like the English track and trace system. No prizes for guessing where the axe is going to fall, or who it will most affect. Well-off students will always be able to study abroad.

As the UK leaves behind Erasmus and charts a more insular course in the world, opportunities are closing off for poorer students. Their world is becoming smaller, and hollow claims of a “global Britain” will turn out to be as much of a betrayal of poorer people as every other aspect of Brexit. I feel sick to my stomach at the inevitability of this future for young people in England. But it is not inevitable for all parts of the UK.

At the time of writing, the Scottish Government is seeking a special arrangement with the UK Government that will allow students at Scots institutions to continue to participate in Erasmus. Northern Irish institutions will be supported in this way by the Irish Republic. If the answer for Scotland – as I suspect it will be – is no, then for the sake of the majority of younger Scots, an internationalist, independent, European Scotland cannot come soon enough.