A Christmas Eve Nightmare: Peebles, 1629

The Tolbooth of the Royal Burgh of Peebles, which served as the town jail in the 17th century, was an “imposing stone structure” located at the foot of the Bridgegate beside the Eddleston Water, known as the Cuddy. Comprising basement rooms and an attic, the front of the building measured twelve metres long and stood on the site of the modern-day Bridgegate flats. It was in the Tolbooth in the mild spring of 1629 that twenty-seven local women, men and children were gathered and locked up, awaiting trial. Their charges? “Meeting at night for nefarious purposes”, “making a pact with the devil and denying their baptisms”, “frolicking with Auld Nick”, and “laying sickness on their neighbours”. In other words, these twenty-seven local people were accused of witchcraft, and some of them would pay a heavy price for their alleged misdemeanours. The final executions took place on Christmas Eve, 1629.

What happened in Peebles in 1629 was a tragedy – yet most people know almost nothing about it. One interpretation of what happened is set out in Borders Witch Hunt (Mary W. Craig, 2020). Using Craig’s insightful text, local knowledge, and a variety of other historical sources, we can piece together a grim tale of fear, panic and injustice which culminated in the brutal execution of innocent people right here in our sleepy Tweed Valley. What happened here was part of a wider pattern of misogynistic, superstitious alarm that gripped Scotland and northern Europe for almost a century. Across Scotland, nearly 4,000 people were tried under the provisions of the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 – most of them women – and two thirds were executed.

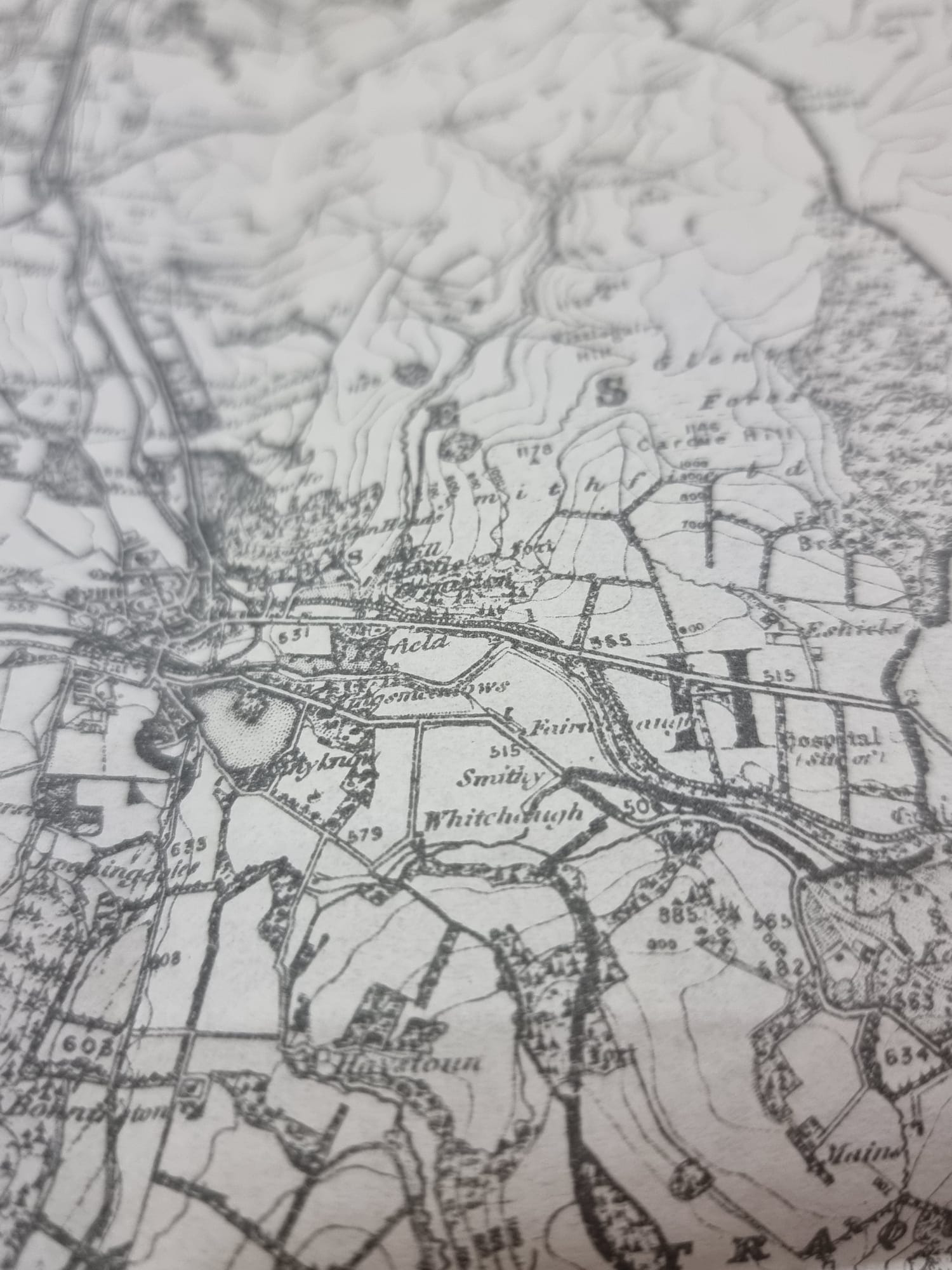

Peebles in 1629 would, on the surface, seem loosely familiar to many who know the town now. The High Street would be there, running east to west, as would the Bridgegate, the Northgate, and the old town. The old burgh wall, a section of which still stands in the East Station car park, would stand complete, limiting access to the royal burgh – a town affected like many others by the plague, and deeply suspicious of outsiders. And the land around us – Hamilton Hill, Venlaw Hill, Cademuir, Gypsy Glen and the Drove Road and the Tor Hill – would all be much the same, with their familiar contours and their place in our imaginations. And yet, culturally and politically, it is hard to imagine the environment seventeenth century Peebleans were living in. Charles I had occupied the throne for only four years after the fifty-seven year reign of his father, King James VI. James – an otherwise intellectual monarch in his time – had suddenly become obsessed with witchcraft when the vessel carrying him and his new wife, Anne of Denmark, to Scotland was damaged in violent storms at sea. James became convinced that the storms were an attempt on his and his wife’s lives, and that the waves had been conjured by those who wished him ill. Thus began a national crusade against “witches” in Scotland, with the monarch harbouring a paranoia so intense, he even wrote a book about witches and black magic called Daemonologie, published in 1597 and reprinted again in 1603 when he took the English throne. Daemonologie, and its anxious ravings about everything from witches to vampires, became national doctrine. Against this background, in a pre-enlightenment Scotland, it is easy to imagine how terrified people could become by the perceived threat of sorcery.

And so it was that in 1629, Peebles was gripped by gossip. It was the talk of the steamie that a handful of locals had been acting suspiciously. The paranoia about witchcraft had already touched the town – two years earlier, according to Clement Gunn’s volumes, the Book of the Cross Kirk AD 1560-1690, a Peebles woman called Margaret Dalgleish had been accused of witchcraft, but had got off with only an admonition on the condition she sought pardon from God. But the anxiety returned in 1629 with a renewed vigour. Craig captures the zeitgeist of the local murmurs when she speculates on the locals’ musings: “Why did Katherine Wode and Marion Boyd always hurry down to Tor Hill, ignoring their neighbours’ greetings?” Other causes for concern were Patrick Lintoun, who “yawned all morning” when he had no reason to be tired had he been in bed all night as he should, and three others including Gilbert Hogg and Janet Hendersoune who missed the Sunday church service two Sabbaths in a row – imagine! Rumours grew arms and legs and all sorts of anecdotal evidence compounding the suspicions sprang up. Accusations by the court of public opinion were like an avalanche; one claim that someone had been absent from church due to illness led to another person “remembering” they’d seen the culprit out and about, looking well, which led to another person saying they’d seen them out after nightfall. It’s not hard to see, in such a febrile, paranoid community, how things got out of control. Craig explains that the presbytery of Peebles was called to discuss the happenings, meeting late into the night to discuss what to do about the rumours, and form a list of all the suspects. After agreeing to secure leave from Edinburgh to conduct a trial, which came within the week, twenty-seven local people “vehementlie suspect of wytchcraft” were rounded up and thrown in the Tolbooth. Their names were, according to Craig:

Agnes Chalmers, Sussanna Elphinstoun, Margaret Yerkine, William Thomesoun, William Mathesoun, Thomas Stoddart, Agnes Robesoun, Katherine Broun, Marie Johnestoun, Janet Hendersoun, Agnes Thomesoun, Katherine Wode, Marion Crosier, Issobel Haddock, Gilbert Hogg, Jean Watsoun, Margaret Dicksoun, Margaret Johnestoun, Janet Achesoun, Bessie Ur, Katherine Alexander, Helen Beatie, Margaret Gowanlock, Marion Boyd, Katherine Mairschell, Patrick Lintoun, and John “Joke” Graham.

The accused were from Peebles itself, Stobo, Lyne, Blyth Bridge, Romanno Bridge, and West Linton. Some of the accused had previous charges against them. According to Clement Gunn, Janet Hendersoun had three years earlier been accused of sinning and “was ordered to stand for six Sabbath days at the kirk door and place of public repentance at the kirk of Linton, clothed in sackcloth, and with bare feet.” Every one of the twenty-seven accused in 1629 maintained their innocence. Some of the suspects had known what was coming and had attempted to flee towards Innerleithen or Biggar, but all were caught and rounded up. When the Tolbooth was full, the remainder of the group was locked in the kirk. All were to be questioned and tried by local commissioners and the minister of the presbytery of Peebles, Archibald Syd.

After many days and nights of intense questioning and accusation, the first to crack was Issobel Haddock from West Linton, described, according to Craig’s sources, as a young girl. Under the intense pressure of the minister and his officials, this young, very likely sleep-deprived woman, held in the mouldering basement of the Bridgegate tolbooth, finally caved and gave a false confession to say that she and others had met the devil on Tor Hill (on the right as you travel from Peebles to Kailzie), and she was prepared to name names, most likely in the desperate hope of leniency for assisting in the unrelenting inquisition. And soon after, writes Craig, “all the others broke down and also confessed” to the absurd accusations, going into extraordinary detail about “what the devil looked like, what his voice was like, and what he had promised them”. The town descended into uproar when word got out about the confessions. Half the town wanted blood, having “always known” of the guilt of the accused, while the other half staunchly defended the accused in the safest way they could with the threat of death hanging in the air: they dismissed the allegations as gossip and spoke of their good characters.

Finally, on 11 June, Reverend Syd was satisfied that there was enough evidence to commence a formal trial. The accused were brought before the court of the presbytery, and the male jury drawn from the burgh, in the Tolbooth and had their charges read against them. Exhausted after weeks of uncomfortable imprisonment, with no defence to speak of, many had to sit on the stone floor of the court room, dishevelled and unkempt – conveniently for their accusers, looking more like “witches” and nefarious undesirables than ever before. Twenty-four of the group were found guilty. Ten days later, they were marched barefoot up the Calf Knowe (part of Venlaw Hill), strangled by rope, one by one, and then burned in tar barrels. The sight and smell of the burning corpses must have been gruesome beyond imagination.

Three of the accused – Sussanna Elphinstoun, Margaret Johnestoun, and John “Joke” Graham were spared execution because the jury had found the charges against them “not proven” – a verdict unique in Scots Law which is under review today. They continued to be detained in the tolbooth until the end of the year due to the legal system being preoccupied with witch trials elsewhere. Finally, a new trial was held on 22 December 1629, and the now-wretched accused, ragged and malnourished after months of rudimentary imprisonment, were once again brought before the presbytery and the jury, whom Craig writes were “under pressure no doubt to correct their previous mistaken verdict”. This time, Reverend Syd got the verdict he wanted. The remaining three were to be executed. On Christmas Eve, 1629, the public of Peebles gathered once again and watched Sussanna Elphinstoun, Margaret Johnestoun and John Graham burn in tar barrels. According to Craig, the spectators then turned, led by Reverend Syd and no doubt stinking of smoke and burning flesh, and headed back down the path to the church to celebrate the birth of Christ.

What is striking about the 1629 executions in Peebles is this: the crime twenty-seven local people were executed for – witchcraft – is something that doesn’t exist. We know this now. In 2021, we can say with absolute certainty that whatever those twenty-seven people may have said or done, they were not witches. They did not “frolick with Auld Nick”. They did not speak to the devil. Those are facts. At worst, the twenty-seven victims of the Peebles witch trials of 1629 were guilty of petty grievances with one another – a natural occurrence in times of strife and pestilence when food and resources are in short supply. And yet, those twenty-seven people were executed. Trial records would support this; too often, the occupations of the accused are listed as “vagabond” and their social status “landless”. The records paint a picture of social injustice, disenfranchisement, and a deep-seated misogyny which was state-sanctioned, with preacher John Knox’s 1588 pamphlet The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women illustrating the basis for a widespread suspicion and hatred of women that ultimately caused death and suffering to thousands.

Throughout those dark years of the Scottish witch trials, Craig’s research suggests there were forty-one executions in Peebles alone. Nine accused suffered other punishments, and one was acquitted. Three were executed down the road in Innerleithen, and the fate of dozens more across Peeblesshire is lost in the fog of time. Edinburgh University have published an online interactive map which shows the names, residences and other known details about each victim. Looking at the map highlights the terrifying scale of the witch trials in Scotland and it does beg the question – why do we not yet have a national memorial to the memory of those murdered by a paranoid, superstitious state? Perhaps the Borders would be the best place to locate such a memorial, being as we are the region outside of Edinburgh with the most witch-related executions in Scotland. It is not a superlative we Borderers can ever be proud of, but it is perhaps worthy of consideration now that the Scottish Parliament is set to consider pardoning victims of the witchcraft trials.

However we may or may not choose to remember the victims of the Scottish witch trials, the story of Peebles in 1629 is a deeply moving one for all who live in this town. The names of the accused are the names of local families in our communities. We all know of Thomsons, Hendersons, Johnstons, Boyds and Grahams. These are not faraway “others”; they are our own flesh and blood. So this Christmas Eve, when people in Peebles are making merry, I’ll be raising a glass to the “Christmas Eve three” – to Sussanna, Margaret, and John.